How Machines Hear: The Magic of Audio Fingerprinting by Anjan Sampath on January 27, 2026 121 views

You’re sitting in a cafe, chilling ☕ — where the drinks are overpriced and the atmosphere is a mix of music, chatter and one guy whose laugh sounds like an engine starting. 🚗

Suddenly, a song starts playing and you know you’ve heard it before. But from where? So you pull out your phone and open Google. Tap “Search a song” 🎶

Hold it up. 🤳

Two seconds later – boom! It knows the song. 🤯

Nice! But how did the phone get the song’s name through all that noise, chaos, and someone coughing directly into your microphone? 🤔

How does this magic work? 🧙♂️

This is something called as audio fingerprinting. Just like every person has a unique fingerprint, every song has a unique “sonic fingerprint.” An audio fingerprint is a compact, unique representation of an audio file or stream. Instead of saving the whole track, Google captures the essence or the pattern of the song that doesn’t change if the volume is low or if there’s background noise. So how are these unique fingerprints created?

Let’s Walk Through The Process. 🔎

First is collecting the audio, Of course they need permission from the artists or record labels to get official audio tracks. They also scan publicly available sources like radio, copyright free music.

Then comes preprocessing the audio. Think of this like the prep work before cooking — the raw music can come in all shapes and sizes (MP3s, old radio recordings, even vinyl rips), so everything needs to be cleaned and standardized first. The common preprocessing steps include:

- Convert to PCM: All tracks are converted into Pulse Code Modulation (PCM), the standard raw digital audio format used in computers. This gives the system a consistent starting point no matter what file type the song was in.

- Remove silence: Long quiet gaps at the start or end don’t help in identifying a song, so they’re snipped out.

- Convert to mono: Stereo is great for listening, but for fingerprinting, one combined channel is enough — and it keeps things simple.

- Resample to a fixed sample rate: Different sources use different sample rates (44.1 kHz, 48 kHz, etc.). Standardizing this makes analysis fair and consistent.

- Normalize loudness: Whether the track was recorded too loud or too soft, the system balances it out so volume doesn’t trick the fingerprinting.

- Remove unwanted noise/DC offset: Low-frequency rumble or background noise is filtered out, leaving just the meaningful musical patterns.

Only after these steps do we get a clean, standardized version of the audio that’s ready for fingerprint generation. The next step? Turning the audio into a spectrogram.

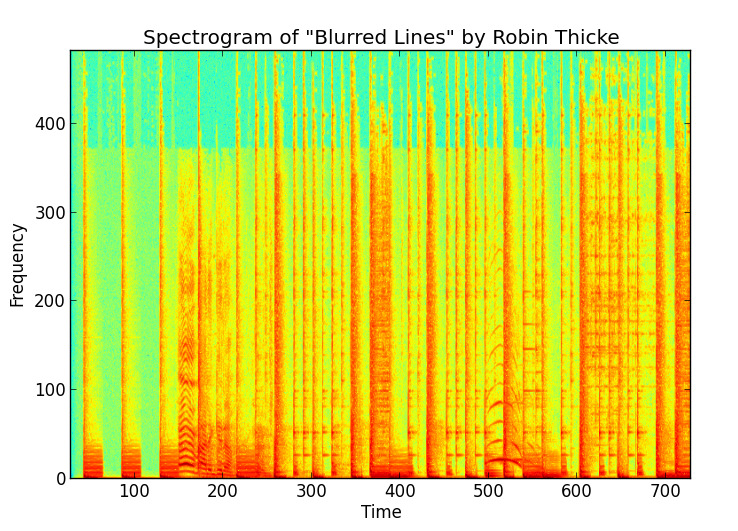

A spectrogram is basically a picture of sound — it shows how the frequencies of the audio change over time. The x-axis is time and the y-axis is frequency, and the color represents the intensity of each frequency at a given moment.

Now we can get into how a fingerprint is created –

1. Picking out peaks: From the spectrogram, the algorithm identifies local maxima the “loudest points” — the strongest frequency points at specific times which remain constant even if the audio is noisy, compressed, or played at different volumes. These peaks are like the main singer in a music video, we ignore the background dancers right?

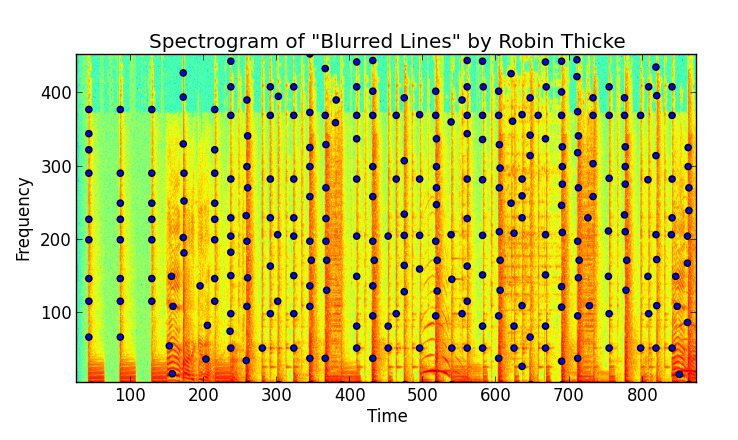

2. Creating a constellation map: Once peaks are figured out, they’re plotted on a time–frequency graph. Picture dots scattered across the graph, where each dot represents a strong frequency at a certain time. The result looks like a starry night sky, except instead of constellations like Orion, you get The Weeknd or Laufey. Each song forms a unique constellation map, just like stars in different parts of the night sky.

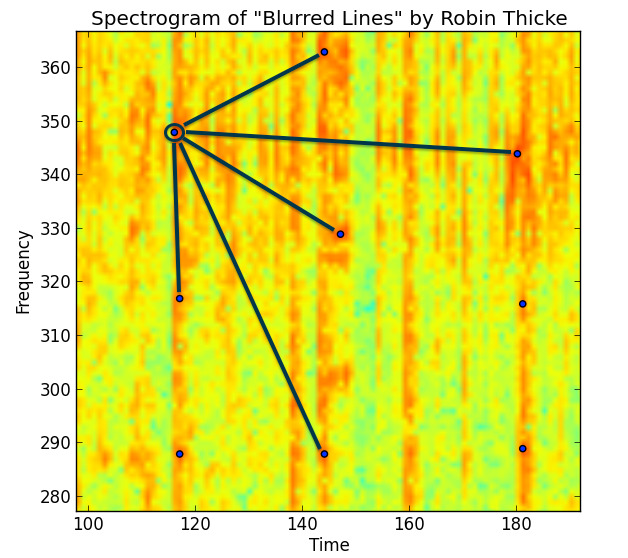

3. Making pairs of peaks: To make the fingerprint more robust, the algorithm doesn’t just look at single peaks. Instead, it creates pairs of peaks within a small time window.

Example: take a peak at time t1 and frequency f1, and pair it with another peak at time t2 and frequency f2 that occurs shortly after.

By linking them this way, the system isn’t just noting which frequencies popped up, but also when they happened relative to each other. That timing relationship is what makes the fingerprint extra reliable.

4. Converting pairs into hashes: Each pair is turned into a compact hash value. Think of it like turning a big detailed description into a short unique tag.

The hash usually carries three pieces of info: frequencies f1 & f2 and time difference (t2 – t1). So one pair looks like: (f1, f2, Δt). Now this tuple (f1, f2, Δt) is converted into a compact integer hash.

- Frequencies and time differences are quantized (rounded into bins, e.g., nearest 1 Hz or 10 ms).

- Then packed into a fixed-length bitstring.

For example :

f1 → 10 bits (0–1023 Hz band) f2 → 10 bits Δt → 12 bits (time up to ~4s) Together → 32-bit hash. So a pair like (430 Hz, 900 Hz, 2.1s) becomes something like:

0001101010 1110000100 100001010010This hash is so tiny (just a few bytes) but highly distinctive. A single song can produce thousands of such hashes.

5. Storing in the database: All these hashes are stored in a hash map (key–value structure) for efficient lookup, where:

Key = hash (f1, f2, Δt) Value = song ID + time offset

Simply Putting It All Together 🧩

So finally we know how millions of songs are converted into hash maps and stored in the database. When you ask Google to “listen,” your phone runs through the very same fingerprinting steps:

- The snippet is preprocessed (converted to PCM,resampled, normalized).

- A spectrogram is made, peaks are spotted, pairs are formed, and hashes are generated.

Then these hashes are sent to the central database and looked up in the hash map. Here’s how the search works:

- Each hash from the snippet points to one or more potential matches (song ID + time offset).

- The system looks at which song gets the most “votes” from these hashes.

- To avoid false positives, it also verifies that the relative time differences between hashes in the snippet align consistently with the same part of the song in the database.

If a large cluster of matching hashes all line up, BINGO! The track is officially identified. 🎉

The best part? You can just hum the tune and it will be recognized (no lyrics needed), as this only depends upon the unique audio fingerprint created by the melody itself. 😮

Why Should Developers Care ? 🤷♂️

Audio fingerprinting is a good example of how to build systems that work in the real world. It demonstrates:

- 🎧 Noise-tolerant feature extraction — pulling out signal even when the data is messy

- ⚡ Hash-based matching — fast lookups at massive scale

- 🗂️ Efficient database indexing — finding the right result in milliseconds

- 🧠 Robust pattern recognition — matching partial, imperfect input to a complete reference

Now you know the complex yet fascinating process your phone runs to identify a track in seconds. Pretty cool, right? 😎 So the next time it tells you what song is playing, remember it’s not just listening, it’s analyzing, comparing, and pattern-matching at lightning speed. All of this happens in seconds, on a device in your pocket. 📳 That’s smart engineering quietly working behind the scenes. 👨💻

If you want to know more in depth about this topic, you can read a deeper, code-focused explanation in this excellent article by Will Drevo.