💰The Memory Vault: Where Your Code Keeps Its Variables by Sufyan Gazdhar on December 22, 2025 158 views

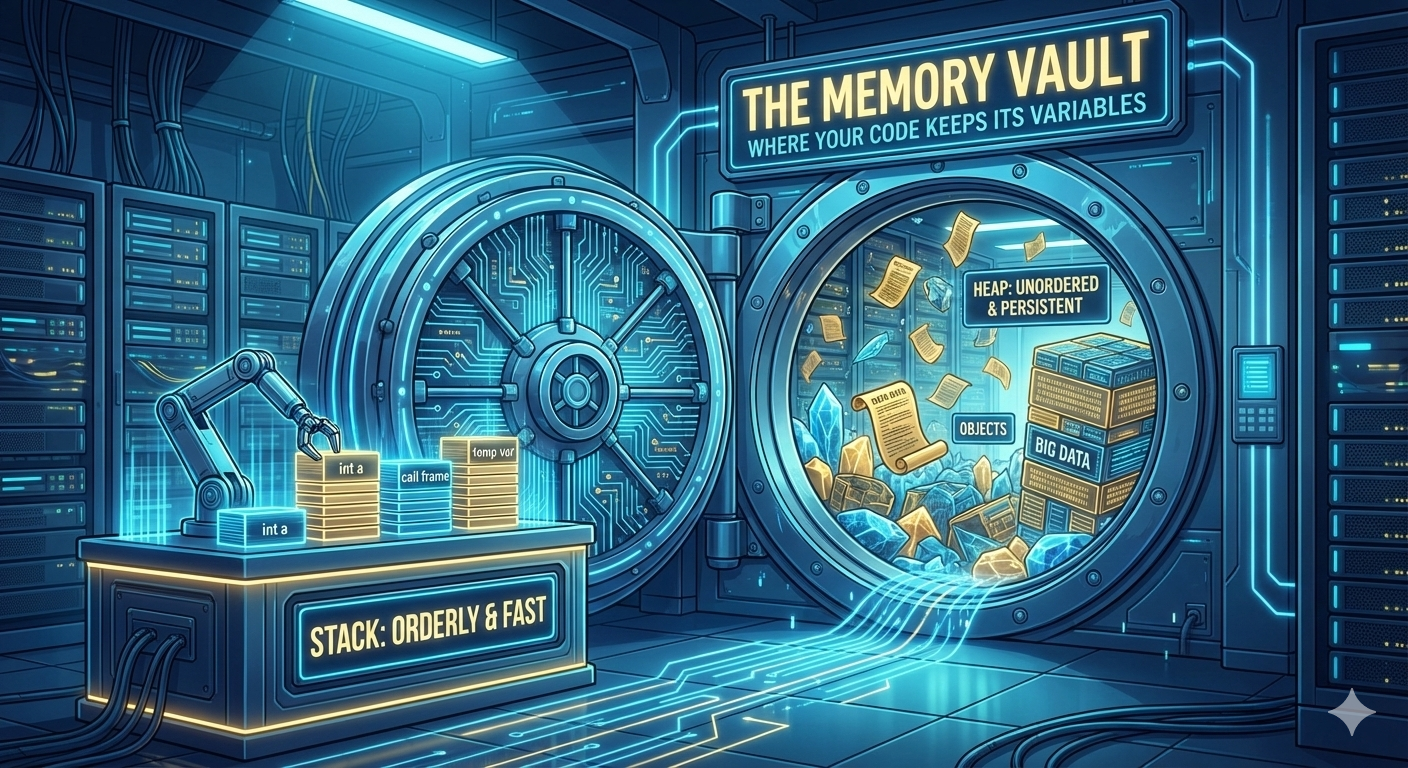

When your code runs, it’s constantly stashing, retrieving, and discarding data, variables that define how your logic behaves. But where does all of this information actually go? Under the hood, your computer has a system, fast, organized, and surprisingly elegant, for deciding where each variable lives, how long it stays there, and how it’s accessed. In this deep dive, we’ll unlock The Memory Vault, revealing how your code uses two powerful storage zones – the stack and the heap – to manage data efficiently. From lightning-fast teller desks to deep vaults with bio-metric locks, let’s explore how modern systems handle variables behind the scenes.

Stacks of cash, Heaps of gold

Imagine stepping inside a high-security bank.

At the front is the teller desk, fast, efficient, and designed for quick transactions. Need to check your balance or withdraw a small amount? That’s handled right there. Deep within the reinforced vaults behind the scenes are the long-term holdings – assets that take more time to retrieve but are essential for the bank’s operations.

Your code follows this same model.

Some data is temporary and needs instant access. Other data must remain safe and available for the long run. This is precisely the job of stack and heap memory.

Let’s explore how your computer handles both, efficiently, securely, and with the right balance of protocols.

🧾 The Front Desk vs the Vault (Stack vs Heap)

Just like a bank divides between teller desks and vaults, your system divides memory into two broad spaces:

| Feature | Stack (Teller Desk) | Heap (Vault Room) |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Short-term, fast-access storage | Long-lived, flexible storage |

| Location | Close to CPU | Further out in RAM |

| Lifetime | Tied to function execution | Persists until freed or garbage-collected |

| Access Pattern | Direct, ordered (LIFO) | Indirect, scattered |

| Speed | Very fast | Slower (cache misses likely) |

| Management | Automatic | Manual or via garbage collection |

⚡ The Stack — Fast & Front-Facing

The stack is where your program handles day-to-day tasks, local variables, function calls, and short-lived operations.

- When a function is called, a stack frame is created.

- As the function exits, the frame is automatically discarded, like clearing a deposit slip after processing.

- It operates on a LIFO (Last In, First Out) basis.

- Each thread has its own stack, so there’s no data collision.

❓ FAQ: What happens to stack variables after a function returns?

They’re erased when the stack pointer moves back. You can’t access them anymore, unless you made a copy elsewhere.

Because stack memory is so predictable, it lives close to the CPU, often in the L1 or L2 cache, enabling near-instant access.

🔐 The Heap — The Secure Storage Room

The heap is the vault, used for large, long-lived data that must persist across function calls or be accessed globally.

- Objects, arrays, and dynamic allocations go here.

- Access is done through pointers – addresses stored in stack variables.

- Multiple threads can interact with heap memory, which requires coordination.

- Languages like Java and Python use garbage collection to manage this space; C/C++ require manual cleanup

❓ FAQ: Is heap memory always slower than stack memory?

Not exactly. Accessing heap data can still be fast, especially if it’s cached. What’s slower is the allocation and de-allocation process.

❓ FAQ: Why not store everything on the stack?

Stack size is small and fixed. Heap offers dynamic space, essential for big data structures, objects, and flexible lifetimes.

💾 Cache: L1, L2, L3 — Your Bank’s Memory Hierarchy

To understand why some memory is faster than others, you need to understand the memory hierarchy, the layered architecture of access points.

| Memory Level | Role | Size | Access Time | Analogy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 Cache | Right at the teller’s hand | ~32KB | ~1 CPU cycle | Teller’s clipboard |

| L2 Cache | Nearby drawer | ~512KB | ~4–10 cycles | Locked drawer behind desk |

| L3 Cache | Shared among branches | ~10MB | ~12–40 cycles | Secure room behind main floor |

| RAM | Bank’s central storage | GBs | ~100–300 cycles | Vault with bio-metric lock |

| Disk | External storage (swap) | TBs | 10,000+ cycles | Off-site secure storage |

The closer the memory is to the CPU, the faster the transaction. But fast memory is limited, you can’t store everything at the teller’s counter.

❓ FAQ: Is RAM really that slow?

Yes — L1 takes ~1ns, RAM ~100ns. That’s like the teller handing you cash instantly vs driving to a warehouse.

❓ FAQ: Can I control what goes into cache?

Not directly. But writing cache-friendly code, like accessing memory sequentially, helps the CPU pre-fetch efficiently.

🎯 Direct vs Indirect Access — The Hidden Cost of Looking Things Up

Memory access isn’t just about where data is stored, it’s also about how the CPU gets to it.

Stack: Direct Access

Stack variables are like deposit slips sitting on the teller’s desk, their location is fixed and instantly reachable.

The CPU knows exactly where they are, often in its L1 or L2 cache, no detours, no delays.

❓ FAQ: Is the stack always in the CPU cache?

Not always, but because the stack grows predictably and deals with small, short-lived data, it usually ends up in the cache. That’s why stack access is lightning-fast.

Heap: Indirect Access

Heap data is different, your stack variable just holds a pointer to the actual data.

The CPU must follow that pointer into deeper memory layers, which may involve L3 cache, RAM, or even swap space.

❓ FAQ: Why is heap access slower?

Because the CPU has to follow the reference and fetch from further away. Think of it like asking the teller to open the vault and retrieve something from the back room, it takes time.

🧭 Stack and Heap in Action

Let’s trace exactly what happens, step by step, when your program executes this simple line of code. The process reveals the intricate dance between the stack and the heap.

Account a = new Account("Gold");- Requesting the Vault (Heap Allocation): The new Account(“Gold”) expression tells the system it needs to create a new object. Since objects are complex and can have long lifetimes, this memory must be allocated from the heap. The memory manager finds a suitable free block of space in the heap.

- Initializing the Object: The Account object’s constructor runs, setting up the initial data within that newly allocated heap memory.

- Getting the Key (Address): The memory manager returns the memory address of the newly created Account object. This address is like the unique key or location code for a specific box in the bank’s vault.

- Stashing the Key (Stack Allocation): The program needs a place to store this key. A variable named a is created on the stack. The value stored in a is not the object itself, but the memory address pointing to the object on the heap.

Now, let’s see what happens when we use this variable:

System.out.println(a.getBalance());- Find the Key: The CPU needs to find the getBalance() method. To do this, it first looks for the variable a on the stack. This is a fast, direct lookup.

- Read the Address: The CPU reads the value stored in a– the memory address of our Account object in the heap.

- Go to the Vault: The CPU uses this address to access the actual Account object stored in the heap.

- The Potential Delay (Cache Miss): The CPU checks its fastest L1 cache to see if the data from that heap address is already there. If not (a cache miss), it must fetch it from the slower L2 cache, L3 cache, or all the way from main RAM. This trip to fetch the data is what causes the delay associated with heap access.

- Execute the Code: Once the object’s data is loaded into a cache close to the CPU, the getBalance() method can finally be executed.

❓ FAQ: What does “delay” actually mean in practice?

A delay here refers to CPU clock cycles being consumed while waiting for data. L1 cache might return data in ~4 cycles, L2 in ~12, L3 in ~40, and RAM in 100–200+ cycles. During this time, the CPU may stall, doing nothing, until the required data arrives. These delays add up quickly in performance-critical code, especially if indirect heap accesses are frequent.

❓ Why Not Keep Everything at the Teller?

Because speed comes at a cost.

- L1 and L2 caches are built using SRAM – fast but expensive and small.

- RAM uses DRAM – cheaper, larger, but slower.

- The deeper the memory, the greater the delay.

Just like a bank doesn’t store gold bars at the front desk, your system can’t afford to keep everything in the fastest memory. It prioritizes the most time-sensitive tasks, like stack operations, for the “teller counter” (the CPU and its caches).

But not all data fits at the counter, and not all needs to.

Stack memory is perfect for small, short-lived data.

Heap memory, on the other hand, handles large or long-lived data, giving the system room to store, manage, and eventually discard it safely.

❓ FAQ: Can a stack variable become a heap variable?

Not directly, but if it’s returned or referenced beyond its scope, the compiler may choose to allocate it on the heap.

❓ FAQ: Does garbage collection pause my program?

Yes, briefly. Most modern garbage collectors are optimized to minimize pause times, but the cleanup process (especially in large heaps) may cause short interruptions known as “GC pauses”.

🚮 Garbage Collection — Vault Maintenance

For high-level languages, the vault has a janitor.

- The garbage collector (GC) reclaims unused memory.

- It tracks object references and determines which ones are still “in use”.

- Major and minor GC cycles keep the heap tidy, but they come with performance costs.

❓ FAQ: Do all languages use garbage collection?

Not at all. Languages like Java, Python, and Go use garbage collection. Others like C, C++, and Rust rely on manual or deterministic memory management. The model remains, heap memory still exists, but cleanup is your responsibility.

🏃♂️ Escape Analysis — Skipping the Vault Entirely

Some objects look like they belong in the heap, but the compiler may notice:

- They’re used only inside one function

- They’re not shared across threads

If so, the compiler performs escape analysis:

- Keeps the data on the stack instead

- Eliminates pointer indirection and reduces allocation overhead

- Avoids heap allocation and GC altogether

❓ FAQ: Can the compiler really move heap allocations to the stack?

Yes. Escape analysis can detect when it’s safe, leading to big performance wins.

❓ FAQ: Does every language do this?

No. Some languages (e.g., Rust) use different strategies like ownership and lifetimes.

📝 Summary: Stack & Heap in the Bank of Memory

| Feature | Stack (Teller) | Heap (Vault) |

|---|---|---|

| Speed | Instant (L1/L2 cached) | Slower (cache/RAM-dependent) |

| Allocation | Automatic per function | Manual or GC managed |

| Access | Direct (offset-based) | Indirect (via pointers) |

| Scope | Per thread | Shared |

| Lifetime | Short-lived | Potentially long-lived |

| Use Case | Locals, call frames | Objects, arrays, shared data |

🏁 The Final Ledger: Key Takeaways

Before you go, here are the essential rules of the Memory Vault:

- ⚡ Stack for Speed: The stack is your fast lane. Use it for temporary, local data that you need instantly. Think of it as your teller’s-desk clipboard, quick, simple, and cleared after use.

- 🪙 Heap for Holdings: The heap is your long-term storage. Use it for large objects or data that must outlive a single function. It’s the secure vault where your most valuable assets are kept.

- 🗝️ Pointers are Keys: A variable on the stack often holds just a “key” (a pointer) to the real data in the heap. Remember that using this key to access the vault takes a little extra time.

- ⚖️ Know the Trade-Off: Every memory decision is a balance between speed and size. Smart programming means knowing when to keep things at the counter and when the trip to the vault is worth it.

Pro-Tips & Common Pitfalls:

- 💥 Stack Overflow: The stack has strict limits. Deep recursion or oversized local data can cause a stack overflow, crashing your program abruptly.

- 🕳️ Heap Leaks: The heap may be large, but it’s not endless. If you don’t free unused memory or still hold references to obsolete objects, you risk memory leaks and out-of-memory errors.

- 🔄 Multi-threading Mayhem: The heap is shared across threads. If two threads modify the same heap object without coordination, you get data races. Use locks, semaphores, or thread-safe structures to stay safe.

🔐 Invest wisely, and may your code run fast with compound returns.